From "Candyman" to Candy Rackets: Chicago’s Sweet and Sinister Past

- Chicago Movie Tours

- 1 day ago

- 4 min read

A van named "Candy Man" sparked a dive into Chicago’s past, where 1920s candy jobbers mixed sweet sales with racketeering and violence.

One evening, while driving through Chicago's western suburbs, I pulled up behind a white van named "Candy Man."

After doing a double take, two thoughts came to mind:

Does this company realize it shares a name with the 1992 horror movie Candyman, filmed on location in Chicago?

Did this business purposely name itself after said horror film?

Honestly, every possible answer here is amusing. But I'd like to think this distributor knowingly named his Chicago-based business after the horror movie Candyman. That would be dark comedy marketing at its finest!

Regardless, the van's name also brings to mind Chicago's deep-routed candy history, which, as you'll see below, turned surprisingly dangerous for some so-called "candy men" in the late 1920s.

We'll use the Maywood Candy Co. as an example.

Chicago's 1920s Candy Jobbers

The small brick building pictured above was once home to the Maywood Candy Co., a wholesale candy distribution business founded around 1920 at the height of Chicago's candy boom.

From what I can tell, the business, located in Maywood, IL, ceased operations around the early 2000s.

By all accounts, the Maywood Candy Co. lived a quiet existence. However, the years spanning roughly 1927 to 1930 must've been nerve-racking ones for its owner and select colleagues.

In the late 1920s, the founder of Maywood Candy Co.—along with with approximately 250 other local candy distributors—is listed as a member of the Candy Jobbers Association of Chicago.

These jobbers, or wholesalers, purchased candies from manufacturers and dealers in Chicago, New York, Boston, and other major U.S. cities. Then, they sold and delivered their goods, via automobile and wagon, directly to candy retailers throughout Chicagoland.

At the time, the Candy Jobbers Association of Chicago's collective business was estimated at $7,000,000 annually—or about $129,000,000 today.

On the whole, the Candy Jobbers Association of Chicago's goals were to twofold:

to make improvements to the candy business

to advance the social conditions of its members

Admirable objectives, I'd say.

But in April 1926, a newly elected leader named Vincent Pastor wanted to make some changes.

Pastor was growing concerned that tobacco dealers who were not members of the association were "selling candy as a side line" after receiving it at a discounted cost. As a result, he proposed a strict amendment to the Chicago Candy Jobbers Association's constitution to induce "tobacco shops to abandon the candy business."

Specifically, Pastor requested all members comply with these rules among a few others:

Do not purchase candy from manufacturers who do not support our association.

Do not purchase candy from subjobbers who do not support our association.

Do not sell to any one who jobs candy and is not a member in good standing.

The Candy Jobbers Association of Chicago, as reported, unanimously approved the amendment.

But in hindsight, it seems as though most members, including Maywood Candy Co.'s, did not fully know what they were getting into.

Chicago's "Candy Racket" Case

In 1926-27, the Candy Jobbers Association's new leader, Vincent Pastor, began to carry out his rules, "actively and aggressively" forcing manufacturers and subjobbers to comply with his terms.

Those who refused were allegedly subjugated to verbal threats and rough handling as well as "assaults and bombings and smashing of store fronts."

All of these actions, along with attempted price fixing, were executed to "terrorize the small dealers, in order to require them to become members."

You'll even find the Chicago candy jobbers listed under "racketeering" in the 1929 book Organized Crime in Chicago. Moreover, some sources like Jazz Age Chicago (2022) claim Al Capone was behind all the violence.

Sheesh.

As a result of the association's "terroristic methods," 45 officials and members—including the founder of Maywood Candy Co.—were initially indicted for enacting violence against competitors and violating the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890, which outlaws monopolistic business practices.

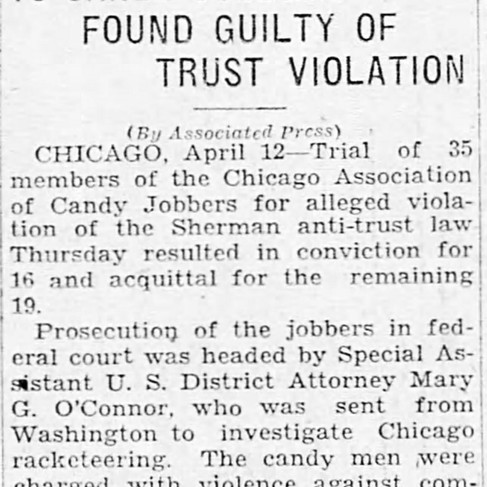

Ultimately, 35 members went to trial. Sixteen members, including Victor Pastor, were convicted and sentenced, liable to a year in prison and fines ranging as high as $5,000 (about $95,000 today).

The 19 other men named in the indictment were acquitted since "evidence did not show their guilt, and interstate commerce [was] not involved."

Since Maywood Candy Co. only appears at the outset of this trial, we can assume either its owner was one of the 10 men who didn't go to trial or he was of the 19 acquitted.

Either way, good news for this Chicago "candy man" and his distribution company.

For many, the name "Candy Man" might conjure up images of a hook-handed horror villain.

But in 1920s Chicago, the real terror came from men in business suits—candy jobbers threatening shopkeepers, smashing storefronts, and fixing prices.

👍